Sketch blog — see all posts

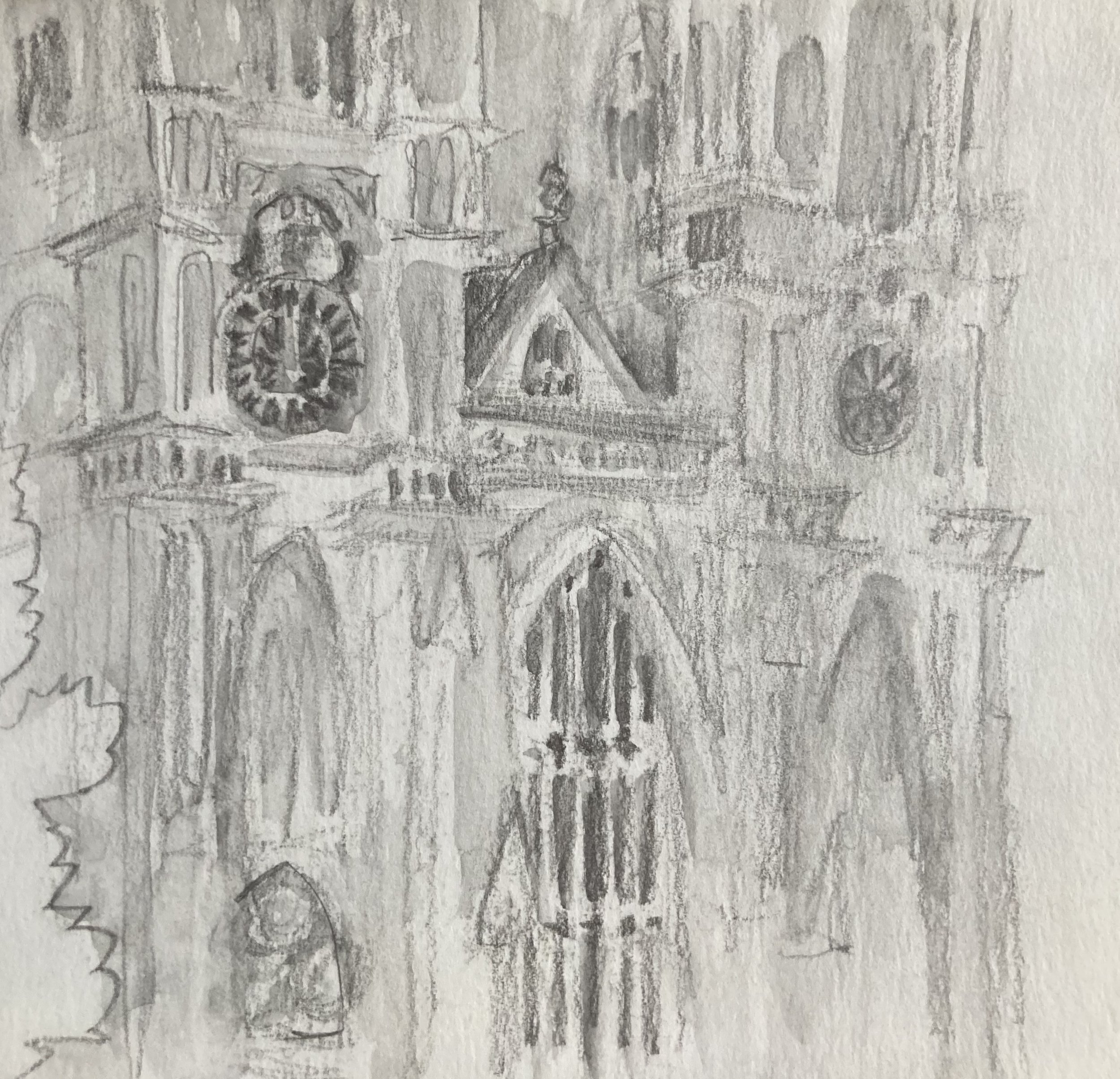

England

/On a dig

/Sketching in the coastal forest with students of the Maine Archaeology Field School, taught by Dr. Bonnie Newsom. The site: a colonial homestead adjoining a Passamaquoddy shell heap. Is that a horse jaw in the pit?

Favorite sheep

/Sequel to favorite cow

Dennysville, Maine

Climbing around the tree of life

/I’m systematically studying systematics—how all living things on Earth are related in a tree of life.

I claim to have a system. But I’m not one to stick to recipes. Rather than ascending the tree in an orderly fashion, I tend to backtrack and change directions, jump squirrel-like to distant branches, and sometimes fall off. More time is spent on tangents than actual taxonomy.

But I know the tree is there; I can come back to it. It’s a guidepost, a framework. It keeps contained and organized a vast realm of biological inquiry that would otherwise be completely overwhelming. It’s a lot like my 3,400-item hierarchical to-do list, which I edit and reshuffle ad nauseam while only occasionally completing an actual task. As mighty as my “Workflowy” list undoubtedly is, the tree of life has it beat with something like 1.8 million species described and 10 million estimated—or maybe 3 trillion, if that makes a difference—not counting untold oodles of extinct ones.

Something I find exciting about this tree is that it’s a new way to orient oneself as a naturalist, despite the fact that the biodiversity it encapsulates is 4 billion years in the making. We may have been identifying and categorizing living things for the entirety of human existence, but we have only had the concept of an evolutionary tree since around the time of Darwin. And the tree itself has evolved dramatically as taxonomists hone the ability to compare organisms at a molecular level. Only within my lifetime has it grown into its current triadic shape, dividing life on earth into three major superkingdoms or domains or whatever you want to call them: Eubacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. (I’ll elaborate on this somewhat in the next post, if I stick to the recipe, at least.)

As we speak, phylogeneticists in our midst are pooling information from 4,185 studies and 148,876 species and counting in the effort to refine not only the branching patterns of the tree but also the timing of those splits between lineages, some of which diverged hundreds of millions of years ago. Regardless of how accurate all of that is at this point, I like having such a tree to think about. It lends an expansive dimension of time to the landscapes and living things I see spread out over global space. It gives me a sense of the familial relationships that intersect with the ecological ones I can observe myself. It’s a Y axis to my X axis of wandering around outside sketching stuff. Lest we fall out of the tree prematurely, I’ll stop here.